This section of the site has newspaper, magazine, or other publications that are connected with the Hermann Fechenbach story.

British Pathé

"Lino cuts of Nazi crimes".

London

65 year old Jewish German artist Hermann Fechenbach. Various shots Fechenbach doing lino cuts. The lino cuts are of German war criminals (Hitler, Goering, Himmler, Streciher) and of Nazi atrocities, they are to illustrate a book about the war commissioned by Stuttgart Town Council.

This is a film of Hermann re-printing this set of lion-cuts as they where cut while interned on the Isle of Man during 1940 and 1941.

The Sunday Times Magazine 23.12.2012

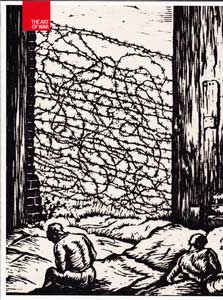

Audrey Ward writes about the artist interned on the Isle of Man in 1940. Hermann Fechenbach's linocut was used as the main introductory image.

A Brush with Life in Exile

During the Second World War, German and Austrian artists fleeing to Britain were held in an internment camp on the Isle of Man. A show at Tate Britain reveals how they created a cultural haven behind barbed wire.

By Audrey Ward

Seventy years ago, on a speck of land in the middle of the Irish Sea, Freddy Godshaw, a Jewish teenager from Hanover, befriended a circus impresario and lion-tamer known as Neunzer. Godshaw, now 89, remembers him as a fascinating character. "He had been to Africa to catch the animals before actually training them. He always carried a little lasso and, for a party trick, he used to pick flowers with the lasso."

The two men were German refugees who, in July 1940; met behind barbed wire in Hutchinson Camp, one of several camps on the Isle of Man. By then, France had fallen to Germany and the British Army had been evacuated from Dunkirk. Growing suspicious of the Austrian and German nationals living in the country, the British government had called for almost 27,000 of these "enemy aliens" to be interned. "Collar the lot," declared the prime minister, Winston Churchill. It appeared that Godshaw, who had escaped to Britain five weeks before the start of the war, and his German friend had swapped one form of restriction for another.

The interns were crammed, 30 men per building, into Edwardian terraced houses on a hill behind the promenade in Douglas, the barbed wire doubling as their washing line. In his new home, Neunzer wanted to dispel the gloom created by the blue-tinted windows and orange light bulbs, which had been painted to prevent bright light being seen from the air.

Using a razor blade, he scraped a series of animal drawings out of the paint so that from his window emerged elegant giraffes, plodding camels, wide-mouthed hippos and elephants' bottoms. His fellow internees followed suit and Godshaw vividly remembers more windows appearing around the camp, "with images of landscapes, flowers and erotic female figures".

It soon became clear that this camp was very different to any other. Within days of Godshaw's arrival, the grassy lawn of Hutchinson Square was teeming with German and Austrian intellectuals, scientists, musicians, Oxford and Cambridge professors, authors and artists, all of whom had been thrown together on this remote island by pure chance.

As magnificent as Neunzer's circus animals were, his artistic endeavours paled when compared with those of the other accomplished — and in some cases internationally renowned artists who had arrived. The Viennese sculptors Siegfried Charoux and Georg Ehrlich were cast alongside the likes of the German-born painter and writer Fred Uhlman and Erich Kahn, an expressionist.

"They were refugees because their work, Jewish origins and/or their political beliefs had put them at odds with the Nazi regime. Hitler condemned modern art as 'degenerate' and ridiculed it," according to Yvonne Cresswell, curator of social history at the Manx National Heritage organisation.

However, it was Kurt Schwitters, one of more than 300 artists who came to Britain between 1933 and 1945 to escape the Nazis, who would become the main star of the camp. "Not only was he a famous artist, but he wrote poetry and was a marvellous raconteur," says Godshaw. With his tendency to sleep under his bed and his love of intermittently barking like a dog, he raised the spirits of his fellow internees. Schwitters, who is perhaps most renowned for his collages, or Merz pictures (a term he invented that referred to the making of new works out of old fragments), had fled Germany to Norway. When Hitler invaded he caught the last fishing boat out of Scandinavia, surviving a torpedo attack before arriving in Scotland. He was then taken to the Isle of Man to join nearly 1,200 other German and Austrian refugees.

Artistic materials on the island were scarce, but this didn't stop Schwitters and his fellow internees from making the best of what they could find. They dismantled a piano, tore up linoleum from floors, collected stamps, toilet paper and other debris. Hellmuth Weissenborn, who would go on to work as a printer after his release from the camp, mixed margarine with graphite from pencils to create an ink for printing. He so used a washing mangle as a press, while Kahn sketched on the back of cigarette packets.

Schwitters also pilfered from the half-empty breakfast bowls of his fellow internees for the sake of his art. In his memoirs, Uhlman recalls the day in October 1940 when he went to Schwitters's makeshift attic studio to have his portrait painted: "The room stank. Of musty, sour, indescribable stink that came from three dada sculptures, which he had created from porridge. The porridge had developed mildew and the statues were covered with greenish hair and blueish excremcnts of an unknown type of bacteria."

Schwitters's porridge sculptures didn't stand the test of time. Thankfully, many of his other works created before, during and after his internment years did survive.

This winter, an exhibition at Tate Britain in London will bring these works, which have inspired the likes of Damien Hirst and Antony Gormley, into the spotlight. Entitled Schwitters in Britain, the exhibition will cover a 30-year period and include about 20 of the 200 works created by the artist while on the Isle of Man.

Schwitters worked on landscape drawings, paintings and portraits of his friends and fellow internees, some of which he sold to his sitters for £5 each (the equivalent of about £250 today). Godshaw, who himself was drawn by Schwitters days before he left the camp, recalls the speed at which he worked. All these years later, the pencil sketch is one of his most prized possessions.

Much of Schwitters's art is easily identified as belonging to a specific period. "You can trace where Schwitters was by looking at his works and what he used in them," says Dr Jenny Powell, assistant curator of modern British art at Tate Britain. "In the internment camp, you can see letters that say 'censored' in the collages." One of his abstract collages from this time features half a ping-pong ball. Powell imagines the internees playing with the ball on the lawn, then Schwitters stealing it to use in his work.

The exhibition will also display a select few pieces from an album containing the works of 18 other artists who were interned with Schwitters. They deserve the attention, given that they too helped to create one of Europe's most extraordinary and influential cultural scenes.

The album was a gift from the internees to the camp's commandant, Captain HO Daniel, and it has been loaned to Tate Britain by Daniel's son, Peter. It includes landscape oil paintings, cartoons poking fun at Daniel, and paintings of half-naked dancing ladies. Schwitters's contribution — a small, abstract oval picture — and Hermann Fcchenbach's lithograph, which depicts two internees in a barn, caged in by the barbed wire, will be shown.

The abundance of artistic activity in the camp was in no small part due to Daniel's support. He provided the internees with materials such as paint, oils, watercolours and paper. Peter Daniel, a sprightly, bearded man in his eighties, was 16 when he arrived at the camp with his parents. "Without my father, there would be nothing here," he says, pointing to the album of art. He recalls his father turning one of the buildings in Hutchinson Square into a studio where the artists could work. "He made it possible for the internees to continue with their art," he says proudly.

During the internment, Klaus Hinrichsen was another champion of the artists. Having fled to Britain during the 1930s to escape Nazi persecution, he spent 11 months in Hutchinson Camp. He helped to found what became known as Hutchinson University. Each evening, lectures were held in subjects such as philosophy and theology. "We had 52 professors in that camp," says Godshaw.

As head of the cultural department, Hinrichsen curated two art exhibitions. One took place in September 1940. The second show, held two months later, featured work by Schwittcrs and the sculptor Ernst Muller-Blensdorf, whose relief panels were carved on mahogany salvaged from a piano. The artists were turning their attention to making money at this point and the camp's newspaper stated that "this time" they were offering their works for sale.

The comedian and author David Baddiel has written a novel, The Secret Purposes, about life on the Isle of Man during internment. 'A really : extraordinary thing about the whole process was that most of the people who got out of Germany were fairly eminent," he says. "The easiest way to get out of Germany was if you had supporters in Britain, who could apply to people in Germany who were professors and artists and important musicians.

As a result, on the Isle of Man, you had six or seven Nobel prizewinners and the Amadeus Quartet. Left to their own devices they set up a university, held opera recitals and, within a week, it's Vienna on the Isle of Man."

Baddiel's book was inspired by his grandfather Ernst, who spent 18 months on the island. Ernst's letters from the camp have been translated from German into English and relay how he went to the lectures, attended the music recitals and met lots of interesting characters. "One of the things he said about it, which was kind of unusual, was that it was great." However, Baddiel is unwilling to give the impression that the internees' lives were bliss. "I don't want to make it too much of a cakewalk. My grandfather lost everything in Germany. After the war, he became clinically depressed. I wouldn't blame that on the internment, but just the trauma in general. A lot of his friends in Germany were murdered. He ended his life as a porter, working in Cambridge colleges. He was devastated."

Although it was a difficult time for many, Godshaw claims that Schwitters — and some of the others — didn't bother to apply for release when the time came. "He was comfortable there. He could paint all day without having to worry about money or other such things. He also had a captive audience for all his poetry recitals and stories.'

Within three months of his arrival on the island, Godshaw and the other internees were encouraged to apply to be released, as the immediate threat of an invasion had passed. He was one of the first to be allowed to leave, and his friend Neunzer was given permission to return to his wife, who was struggling to manage the lions by herself.

Soon afterwards, Schwitters wrote a letter to his wife, Helma. "I am now the last artist here, all the others are free. But all things are equal. If I stay here, then I have plenty to occupy myself. If I am released, then I will enjoy freedom... You carry your own joy with you wherever you go."

He was finally released on November 21, 1941 and, after a spell in London, he moved to the Lake District, where he died seven years later. Hutchinson Camp, having originally held Austrian and German internees, later went on to hold military prisoners of war before closing in 1944.

Looking back on those four months in captivity, Godshaw has fond memories.

"It was no hardship for youngsters like me. I can only say that they were probably the most interesting months of my life."

It was also a prolific time for the artists. Despite a letter from Schwitters and 15 of his fellow artists to the New Statesman and Nation in August 1940, declaring, "Art cannot live behind barbed wire", they were proved wrong. Amazingly, with the help of Daniel and through the artists' own ingenuity, their art not only lived but thrived.

■ Schwitters in Britain is at Tate Britain, London SW1, January 30-May 12,2013

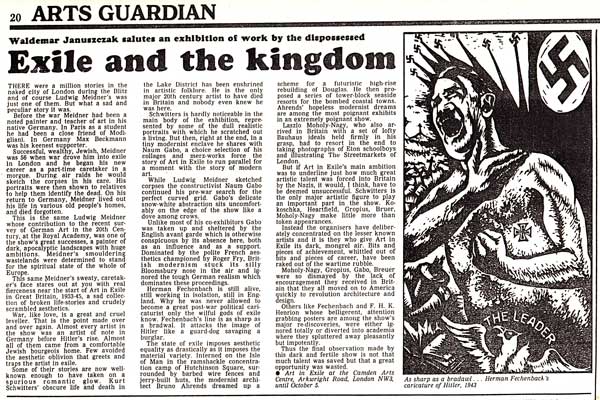

Guardian Newspaper, August 28 1986.

Hermann Fechenbach not only gets the main image but what a write up!

Waldemar Januszczak salutes an exhibition of work by the dispossessed

Exile and the kingdom

THERE were a million stories in the naked city of London during the Blitz and of course Ludwig Meidner's was just one of them. But what a sad and peculiar story it was.

Before the war Meidner had been a noted painter and teacher of art in his native Germany. In Paris as a student he had been a close friend of Modi-gliani. In Germany Max Beckmann was his keenest supporter.

Successful, wealthy, Jewish, Meidner was 56 when war drove him into exile in London and he began his new career as a part-time caretaker in a morgue. During air raids he would sketch the corpses in his care. His portraits were then shown to relatives to help them identify the dead. On his return to Germany, Meidner lived out his life in various old people's homes, and died forgotten.

This is the same Ludwig Meidner whose contribution to the recent survey of German Art in the 20th Century, at the Royal Academy, was one of the show's great successes, a painter of dark, apocalyptic landscapes with huge ambitions. Meidner's smouldering wastelands were determined to stand for the spiritual state of the whole of Europe.

This same Meidner's sweaty, caretaker's face stares out at you with real fierceness near the start of Art in Exile in Great Britain, 1933-45, a sad collection of broken life-stories and crudely scrambled aesthetics.

War, like love, is a great and cruel leveller. That is the point made over and over again. Almost every artist in the show was an artist of note in Germany before Hitler's rise. Almost all of them came from a comfortable Jewish bourgeois home. Few avoided the aesthetic oblivion that greets and traps the artist in exile.

Some of their stories are now well-known enough to have taken on a spurious romantic glow. Kurt Schwitters' obscure life and death in the Lake District has been enshrined in artistic folklore. He is the only major 20th century artist to have died in Britain and nobody even knew he was here.

Schwitters is hardly noticeable in the main body of the exhibition, represented by some of the dull realistic portraits with which he scratched out a living. But then, right at the end, in a tiny modernist enclave he shares with Naum Gabo, a choice selection of his collages and merz-works force the story of Art in Exile to run parallel for a moment with the story of modern art.

While Ludwig Meidner sketched corpses the constructivist Naum Gabo continued his pre-war search for the perfect curved grid. Gabo's delicate snow-white abstraction sits uncomfortably on the edge of the show like a dove among crows.

Unlike most of his co-exhibitors Gabo was taken up and sheltered by the English avant garde which is otherwise conspicuous by its absence here, both as an influence and as a support. Dominated by the polite French aesthetics championed by Roger Fry. British modernism stuck its silly Bloomsbury nose in the air and ignored the tough German realism which dominates these proceedings.

Herman Fechenbach is still alive, still working in isolation, still in England. Why he was never allowed to become a great post-war political caricaturist only the willful gods of exile know. Fechenbach's line is as sharp as a bradawl. It attacks the image of Hitler like a guard-dog savaging a burglar.

The state of exile imposes aesthetic equality as drastically as it imposes the material variety. Interned on the Isle of Man in the ramshackle concentration camp of Hutchinson Square, surrounded by barbed wire fences and jerry-built huts, the modernist architect Bruno Ahrends dreamed up a scheme for a futuristic nigh-rise rebuilding of Douglas. He then proposed a series of tower-block seaside resorts for the bombed coastal towns. Ahrends' hopeless modernist dreams are among the most poignant exhibits in an extremely poignant show

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, who also arrived in Britain with a set of lofty Bauhaus ideals held firmly in his grasp, had to resort in the end to taking photographs of Eton schoolboys and illustrating The Streetmarkets of London.

But if Art in Exile's main ambition was to underline just how mcch great artistic talent was forced intc Britain by the Nazis, it would, I think, have to be deemed unsuccessful. Schwitters is the only major artistic figure to play an important part in the show. Ko-koschka, Heartfield, Gropius. Bruer, Moholy-Nagy make little more than token appearances.

Instead the organisers have deliberately concentrated on the lesser known artists and it is they who give Art in Exile its dark, mongrel air. Bits and pieces of achievement, whittled out of its and pieces of career, have been raked out of the wartime rubble.

Moholy-Nagy, Gropius, Gabo, Breuer were so dismayed by the lack of encouragement they received in Britain that they all moved on to America quickly to revolution architecture and design.

Others like Fechenbach and F. H. K. Henrion whose belligerent, attention grabbing posters are among the show's major re-discoveries, were either ignored totally or diverted into academia where they spluttered away pleasantly but impotently.

Thus the final observation made by this dark and fertile show is not that much talent was saved but that a great opportunity was wasted. • Art in Exile at the Camden Arts Centre, Arkwright Road, London NW3, until October 5.

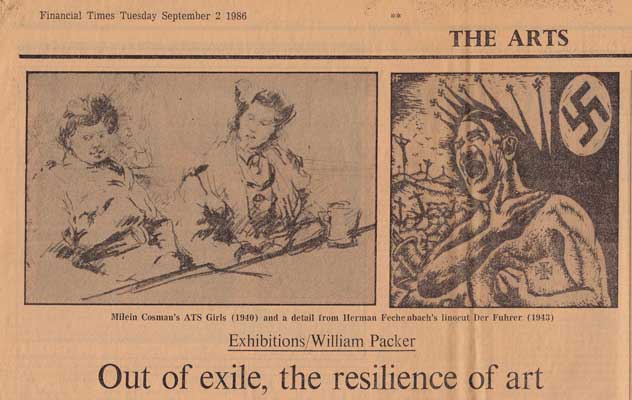

Financial Times September 2 1986.

Although Hermann is not mentioned in the article itself his work featured as one of the main images for the piece.

Exhibitions/William Packer

Out of exile, the resilience of art

The cultural and intellectual diaspora of the 1930s, that was effected throughout what so soon became occupied Europe by Nazi persecution of all that was radical, creatively advanced and, most especially, all that was Jewish, is a well-attested phenomenon of our recent history. But it remains one more usually honoured in terms of general piety, an appendix as it were to the infinitely greater and enveloping horror of the Final Solution, of which it was but one expression among many, than as a particular study.

In terms of our own national life its effects are with us still and, leaving aside the private tragedy and personal cost of such absolute upheaval, have proved to be of an incalculable and wonderfully various benefit. Thus good may indeed come from great evil, to console at least if hardly to justify. In every art, it seems, and in every field of scholarship over a period now of some 50 years, we now may claim as our own the distinguished practice of that extraordinary emigre community.

The exhibition that now fills the Camden Arts Centre (Arkwright Road NW3): (Until October 5), Art in Exile in Great Britain 1933-45, makes the point in the particular case of the visual arts and architecture not merely by paying easy homage to a handful of great or more familiar names, but rather by doing something at once more modest and more useful.

Some of those greater figures are of course quite rightly included but the list is hardly exhaustive. John Heartfield, Naum Gabo, Kurt Schwitters, Laszlo Maholy-Nagy, the architects Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, the photographers Hans Casparius and Felix Man are all well represented, but whether by policy or availability there are one or two surprises. Mondrian, for example, too much a bird of passage perhaps, is altogether absent, and Kokoschka gets only a nominal showing. But this is in no sense to carp or quibble over the selection: here it is for once the famous who supply the context, the mass of minor, unsung, half-forgotten artists of real quality, many of whom have made their homes in Britain ever since, who supply the substance of this admirable and fascinating show.

The project was initiated by the New Society of Fine Arts of West Berlin and, after a showing in Oberhausen, comes to London in a modified form, with major contributions, the fruits of Camden Art Centre's own researches, by some artists not included before. It is set out thematically, section by section, beginning with an impressive group of self-portraits and portraits of other exiles, among which the works of Marie-Louise von Motesiczky, who was given a memorable retrospective by the Goethe Institute last autumn, are outstanding. The small Martin Bloch self portrait, a strangely decorative painting of a woman in a yellow skirt, and an exquisite tiny linocut self portrait by Susan Einzig are all remarkable.

We are then taken on by a somewhat circuitous route through the themes of emigration and actual escape. Indeed one of the most delicate and evocative of all these things is a water-colour by Eugen Hoffman of a family escaping in the night. The ideas and emotions of persecution and exile, the ironical documentation of actual internment in Britain itself, the practice of anti-Nazi propaganda, the topographical observation of the Blitz and, beyond everything, the sense of life continuing with some semblance of normality and the infinite resilience of art itself, are all treated in their turn.

So it is that the most touching and poignant things of all, perhaps, are the most ordinary, in the sense that by them we discover artists who here transcend explicit anger, desperation and — dare one say it in this connection? — self-pity.

Hans Feibusch for example, a fine painter who quite as much as von Motesiczky surely deserves full and wide recognition, shows two religious compositions, Elijah and The Prodigal, both of them fraught with symbolism, and yet it is his painting of a woman simply at rest, Sidonie in Bed, that is the greater work. It might be John Gay with his camera at the fair on Hampstead Heath, or Tim Gidal at a wartime concert at the National Gallery, or catching Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh in a London pub, Walter Nessler painting the moonlit streets of Camden Town, Arthur Segal most exquisitely conjuring up the London fog, Kurt Schwitters the portrait painter or Milein Cosman making a rapid note of ATS girls relaxing in the canteen, but in each case it is the ordinary essential humanity of the experience with which the image is invested that pulls us up short.

It is indeed the resilience and strength of the human spirit that is always most moving, that still gives us hope.

Arts Review 1 March 1985. Volume XXXVII No4.

Guy Burn writes about Hermann Fechenbach at the Blond Fine Art Gallery

Blond Fine Art has at last found a suitably spacious new gallery in Princes Street, the lease at Sackville Street having ended. His first print show is a one man exhibition, a discovery of long hidden talent. Herman Fechenbach is now eighty eight years old, and has had a long frustrating career as a wood engraver and linocutter. The abundant work forms in a way a diary of his sadly disrupted life, where success and fulfillment have evaded his grasp by force of circumstances. His early work in his home town of Bad Mergentheim shows great promise; fairy stories and Jewish life are portrayed. But the loss of a leg in the 1914-18 war was a cruel setback, with years of convalescence. His illustrations for the Hagadah and the plague won him recognition in Germany, only to be snatched away by the advent of the Nazis. Caricatures of Himmler, Goebbels etc., are redolent of hatred. The Children's Train is an emotional record of the long line of trucks on its way to Belsen, crammed with French children who spill out on to the tracks.

He was forced to flee to Israel, and some constructive work was done, notably Call to Lunch showing a Kibbutz girl beating a large iron ring. But Israel did not suit him and he emigrated to England in 1939. Hardly settled here, he was summarily interned in 1940, eventually arriving in the Isle of Man. His delicate wood engravings were no longer feasible and from then on lino was the only medium obtainable. Arrested, Police Station, and Interned are disturbing records of unhappiness in hostile surroundings. The Isle of Man series involving intricate interweaving patterns of barbed wire with the sun shining hopefully through, record a happier time. He starts to use colour blocks: there are blue birds flying in a blue sky, Release found him looking for subjects rather than being dominated by them. His lyrical nudes and peaceful subjects like children in the playground, are brave attempts to grasp normality.

Jewish Chronicle London, 13.10.1972.

Richard Grunberger writes about Hermann Fechenbach's book "The Last Mergentheim Jews'

Forgotten Men

JEWISH CHRONICLE LONDON

RICHARD GRUNBERGER

DIE LETZTEN MERGENTHEIMER JUDEN.

By Hermann Feehenbach.

Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart.. 28 DM.

Bad Mergentheim is a picturesque backwater in Wiirttemberg. Like many places in south-west Germany it had a Jewish community for hundreds of years. There is documentary evidence of Jewish settlement going back as far as 1298. That characteristically was the year of the Rindfleisch massacre—named after a murderous local nobleman—and other nobles persecuted or exploited many subsequent generations of Jews.

Things greatly improved in the nineteenth century, during which the Mergentheim community trebled in size. Alongside a great deal of change there was remarkable continuity of religious observance and professional structure: in 1900 most members of the community were cattle-dealers or shopkeepers and on the Sabbath Jewish business activity ceased.

At about this time Mergentheim also produced its one revolutionary, Felix Feehenbach, a key figure in the Munich revolution of 1918-19, whom the Nazis murdered as soon as they came to power. A few years later they murdered what remained of the community and Mergentheim became juden-rein.

Scattered survivors live in different parts of the world. One of them, the painter, Hermann Feehenbach, who is domiciled in the UK, has written this account ol the Mergentheim kehilla and illustrated it with most moving woodcuts. It is a fitting memorial to forgotten generations who served God and also tried to be good Germans. The former was hard—the latter impossible.

Jewish Chronicle 1 March 1985.

Barry Fealdman writes about Hermann Fechenbach at the Blond Fine Art Gallery

Fechenbach's freshness

The well-planned exhibition of wood engravings and linocuts by Hermann Fechenbach at Blond Fine Art, 22 Princes Street, Wl, is an eye-opener, providing the first comprehensive survey of fifty years of prints by a highly gifted artist who is virtually unknown in this, his adopted country.

Many of Fechenbach's prints are of Jewish subjects, among them Shabbat, festivals, synagogues, folk tales and kibbutzim. Between 1923 and 1930, he made 32 wood engravings to illustrate the Hagada, which he followed with a series of illustrations to Genesis, published in 1969 in a handsome edition by Mowbray. The prints have an expressive power that, combined with a freshness of approach, lends them a notably individual quality.

Guardian (Arts Guardian), March 1985.

Waldemar Januszczak writes about Hermann Fechenbach at the Blond Fine Art Gallery

GALLERIES BRIEFING

Hermann Fechenback (Blond Fine Art, 22 Princes Street, Wl, until tomorrow). Fechenbach was yet another of the young Jewish artists who fled from Hitler's Germany to Britain, and promptly disappeared into that deep, post-war well of obscurity reserved for refugees. These powerful woodcuts are a striking reminder of a forgotten talent, notably when the artist launches a full-frontal assault on the image of the Nazis.

The Times, Feburary 1985.

John Russell Taylor writes about Hermann Fechenbach at the Blond Fine Art Gallery

In London it is pleasant to be able to welcome back two enterprising galleries which 'have had to up stakes in the last few months owing to threatened redevelopment. Blond Fine Art is now in handsome downstairs premises at 22 Princes Street just off Hanover Square, and has a striking selection of wood engravings and lino cuts by Hermann Fechenbach, a German-Jewish artist still happily with us at the age of 88 whose powerful graphic style comes from the same roots as that of Kathe Kollwitz and is often fired by the same anger. Whether in his savage satirical views of Nazi leaders or his documents of internment camp life in the Isle of Man during the Second World War, he is clearly an artist to be reckoned with.

Church Times February 28, 1969.

The reviewer writs about Hermann Fechenbach's book "Genesis'

I recently attended a reception at the Ben Uri Art Gallery, Dean Street, London, to celebrate a remarkable piece of publishing. Genesis (Mowbray, 84s.) consists of the Jerusalem Bible, text accompanied by a powerful series of more than 137 wood engravings by Herman Feehenbach. It makes a handsome book.

Mr. Fechenbach's original woodcuts for the book were on view at the reception, I was looking at the very striking one of Moses when Mr. Arthur Bryant of Mowbray's observed: " Yes, that's Moses—the author."

As for the artist, Hermann Feehenbach has always been fascinated by the great themes of Genesis. He was born in 1897 in Wiuntembuirg, lost a leg in the First World War and gained many artistic successes in several countries before he was forced to abandon his home in Germany in 1939. He subsequently settled in England and has worked in London since 1944:

Black-and-white illustrations are by no means the limits of his work. On the walls also was a selection of his paintings—a brightly coloured, extremely varied output. He seems as much at home with a flower-piece as with a passage of Old Testament symbolism.

© 2021 • Site by numodesign.com